UTERUS/ Walking in Her Shoes: The Eighth Amendment Repealed

First Published in Welsh in O’r Pedwar Gwynt 30th May 2018

https://pedwargwynt.cymru/dadansoddi/gol/diddymur-wythfed-diwygiad

With thanks to editor Sioned Puw Reynolds and Angharad Penrhyn-Jones

We are walking behind a giant uterus. The uterus is made out of pink fluffy material. There are two feet visible underneath. Two wooden poles prop the most magnificent fallopian tubes and ovaries I have ever seen. As we speed up, one ovary keeps on bouncing off my daughter’s head. ‘What is that?’ she asks pointing above ‘Those are called fallopian tubes’ I answer, giving her a very elementary lesson in biology. People around us smile, they can hear the biological terminology in the midst of our Welsh. The uterus knows where she is going (her front is pink gauze). As the midday heat begins to assert itself, the uterus is handed bottled water by other marchers. My daughter is fascinated, she runs in front to say hello to the woman inside: ‘I am worried that she is too hot in there’ she adds. This is September 30 2017, we are on O’Connell Street, Dublin as part of the March for Choice. This is one in a sequence of marches that have already taken place in around the country. We are there in the company of the Meath for Yes group.

Reproductive Rights and Women’s health formed the unremarkable background of my growing up in West Wales in the 1970s. My mother was a district nurse and midwife and during the summer holidays I would spend time with her on her rounds. Mainly I’d be listening to tapes on the flash new stereo in her car while reading comics and downing cans of Fanta.I would also spend time tidying up the sealed coils (IUDs), vacuum packed dressings and syringes into order on the back seat. My mother gave talks on contraception, pregnancy well-being and breast feeding. She was an early advocate of HIV awareness and an experienced practitioner of home deliveries. From a very early age, I was familiar with terms relating to fatal foetal abnormalities such as hydrocephalus and anencephaly. I was also alert to the trauma of teenage pregnancy. In my world, all health care, particularly women’s health care was secular, safe and freely available to all.

I was very happy to settle in Ireland in 2003, however I was shocked by the inequities in health care provision, and the existence of a two tier system (private versus public health). Each GP visit has to be paid for, unless you are on social welfare. Free GP visits for children under 6 were only introduced in 2015. These distinctions in service provision becomes particularly stark when trying for a child. All fertility investigations and support services have to be paid for. Most frustrating to the uninitiated, is how religious beliefs are encrypted in health service provision. Some hospitals are ‘known’ to be more Catholic than others (the Catholic church continues to have representatives on some hospital boards). Certain hospitals would not readily offer amniocentesis or genetic screening, and mothers can often feel judged for asking. Worse still, is that one cannot initially tell whether one’s GP might be pro-choice or pro-life. A GP may have religious beliefs which may impinge upon the medical advice they give. They are not required to make any moral stance transparent.

A GP in Dublin I consulted for fertility testing visibly bristled when she found out that my partner was divorced and that we were trying for a child. When my blood results were returned, I was told that I would never be able to conceive even with a donor egg, and that my own eggs were ‘squidgy’ (her words not mine). She also took it upon herself to chastise me for ‘forcing’ my divorced partner to consider undertaking IVF if necessary. Traumatised, it took me six months to look for another opinion. This time we chose a consultant in the Rotunda, Dublin (one of the busiest maternity hospitals in Europe). Looking at the results[our consultant asked why we had made the appointment. He said ‘these results are perfectly fine, but we can test them again to make sure.’ My bloods were tested once more and everything was indeed normal.

That September day in 2017, as the March for Choice turned from O’Connell Street alongside Dublin’s quays and across the Liffey, the crowd in strong voice started chanting KEEP YOUR ROSARIES OFF OUR OVARIES. Impromptu, my daughter joined in. It was a particularly poignant moment.

The referendum of 1983 authorized the inclusion of the Eighth Amendment into the Irish constitution, an act of incredible cruelty to all women resident in Ireland. The Eighth asserted the right to life of the unborn, equating it with the mother’s right to life. Repealing the Eighth was not only about women’s access to termination for an unwelcome or unviable pregnancy, but how a doctor, consultant or nurse might proceed during a medical emergency. In 2013 additional legislation through an Act of the Oireachtas, ‘The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act’ granted a woman their right to an abortion if there was ‘a real and substantial risk’ to her life. But as Joan Collins TD stated at the beginning of the Repeal the Eighth campaign this meant ‘that medical conditions due to pregnancy that are not in themselves life threatening (e.g. inevitable miscarriage) must be allowed to become life threatening’. This is precisely what happened to Savita Halappanavar who died on 28th October 2012 at University Hospital, Galway. Even though it was clear that a miscarriage was inevitable and Halappanavar herself had requested an abortion, this was denied. The medical team did not judge that her life was in danger. When they eventually did perform surgery, they acted far too late. ‘Yes’ campaigners now want Irish abortion legislation to be named ‘Savita’s law’ in her memory.

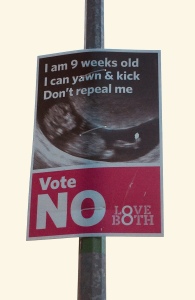

Political campaigns in Ireland have a somewhat oppressive visual impact on the public spaces, that they fill. Large posters are bear down on lamposts. Normally posters feature the faces of politicians. (A friend’s daughter during the last general election asked why there were so many images of missing people on display). During their campaigning the ‘No’ side chose to the feature numerous images of foetuses, frequently titled with accompanied by the plea “Don’t repeal me’. Posters were often placed on roads next to schools and creches. The ‘Yes’ campaign conveyed a more affirmative narrative focused on gobbets of text :’Trust her’, ‘Trust women’ ‘Yes for equality and dignity’ and ‘compassion in a crisis’. Savita’s family had endorsed the ‘Yes’ campaign and her image was also used. Both sides offered personal narratives as a part of their campaigning, but personal stories became key to the ‘Yes’ campaign strategy. In addition to the heart-breaking stories in the media a campaign group ‘In Her Shoes’ (advocating a ‘Yes’) published a small booklet filled with individual stories. These personal histories included accounts of the trauma of having to travel for an abortion, the process of taking illegal medication online and going through an induced miscarriage alone, and the experience of carrying a fatal foetal abnormality to full term.

The vote on the 25th May 2018 marks a seismic victory for the ‘Yes’ Campaign. Given the large mandate, (66.4% Yes over 33.6% No) politicians will be forced to legislate quickly. Importantly, it gives one a sense of the shift that has occurred in Ireland over the last number of decades. As a resident based in Kells (a small market town) in Co Meath, I was particularly pleased to see that the results reflect a shift from the established narrative that rural= conservative. Everybody expected there to be a majority for ‘Yes’ in the urban or metropolitan areas. And there was- the number was 71% overall. However some 60% of rural voters polled were in also favour of repealing the eighth. On seeing the exit polls I tweeted this on the morning of the 26th May:

The exit polls indicate that Ireland does not want to be read as part of a conservative Trump/ Brexit/ extremist or fascist narrative. We refute the patronising way Ireland has been treated by the UK Brexit negotiators and its narrative of exclusion and cruelty

I have no doubt that this is true. Ireland has watched with trepidation the fallout after the UK’s own last referendum. Residents here have been stunned at the degree of ignorance demonstrated by key UK negotiators about Ireland’s geography, history and culture. The world was looking to Ireland during the referendum. I was unable to vote, since only a citizen can vote to change the Irish Constitution. However my application for citizenship was made soon after the March for Choice in September 2017. If accepted, I will now be a far prouder citizen.